A School Governor Writes…

May 12, 2014The following is from a school governor and illustrates elegantly how, in education, those who are meant to be neutral experts can be the most partisan. For reasons of anonymity, the local authority involved has not been named. I have assumed the images used are in the public domain, if anybody knows differently please let me know urgently and I will remove or edit this post.

Well, teachers, you can’t have all the fun to yourselves. We school governors have to undergo training too, you know, especially so that we know what ‘critically friendly’ questions to ask you once a term. My latest experience was a local authority-run, two-hour evening session outlining the new national primary curriculum. There was a lot to pack in, so it was a fairly intense, PowerPoint-heavy evening.

Let me just say up-front that the trainer was a very nice chap. In fact I spent over an hour after the training very pleasantly discussing with him some of what had been said, and it was exactly the sort of intelligent, amiable, open conversation one always hopes to have, but is all too rare. However, it would also be fair to characterise much of the training session as very negative and derisory about much of the new curriculum, and we were very much told what we should think about it; its proponent(s), and what ought to be the objectives of education in general.

I took detailed notes and while some things may be paraphrased I have been careful not to distort the meaning or intended message.

Aim

The aim of the session was stated as:

- To enable governors to understand the background to the new national curriculum and why there are changes from the old.

- To discuss what your school wants to put into place, and how you intend to approach your planning into the forthcoming year.

- To understand how your school has already made a start on planning for the new curriculum.

Knowledge

The trainer had E.D.Hirsch and “knowledge” in his sights from the start. We were told about Hirsch’s Core Knowledge, and that the first draft of the new national history curriculum based on a British version of Hirsch’s model had been “laughable”.

The following slide highlighted the new curriculum’s focus on knowledge:

Could we, the trainer asked, remember any lessons from our own primary education? He answered the question himself with a resounding “no” (spurred on by a particularly earnest, vehemently ‘anti-Gove’ teacher/Governor among us). No, we couldn’t remember any of the ‘knowledge’ we had learned in primary school because items of knowledge were completely transient, something that we learn temporarily and then forget.

The following slide, the trainer said, was the single most important message we were to take back to our fellow governors.

We were to explain to our colleagues that the tree could lose all its leaves in autumn but the next spring would grow new leaves, and he explained how new knowledge was needed for each new job we might have. Should we want to be a doctor, we would acquire all the knowledge we needed for that role. Should we then wish to change career to become a lawyer, or whatever new ‘21st Century’ job came along, we would shed all the old knowledge and acquire the new set we needed. The great irony he said, was that the roots are what are important but that it is the leaves that are testable.

I obtained a copy of an old version of the presentation which came with notes where it was at least superficially acknowledged that both the skills and knowledge are important, but it seems that knowledge is only valued because it provides the context for the acquisition of skills:

It is unnecessary to debate whether the curriculum should only be about subjects, or whether skills are more important than subjects. The tree needs both. The roots cannot develop without the photosynthesis in the leaves, and the leaves cannot grow without the moisture from the roots. They need each other. Each of the skills, competencies and attitudes at the root of learning, needs the context of leaf to develop. Children cannot learn to solve problems unless they have some problems to solve – and these problems occur within the contexts of history, geography, science, technology or any other leaves. Skills cannot be learnt within a vacuum.

Leaves will die if the tree / plant is pot bound

But if the roots are strong, new leaves grow

Lifelong learning is sustained by strong roots not leaves

A further slide illustrates the point:

In conversation later, I pointed out that while I might only remember a handful of my primary school ‘lessons’, I was confident that I still had much of the knowledge I had learned at that time, and that that knowledge had enabled me to build on and learn more. I also cited the Recht and Leslie, 1988 baseball reading comprehension study, where it was found that prior knowledge had a significant positive impact on reading comprehension. The children who knew more about baseball understood the baseball-related text better than those who knew less, regardless of their actual reading ability. “Aah!” He said “that must have been of because they were more “engaged” (i.e. because they must have been more interested in baseball, they ‘related to’ and were more engaged with the task). No, I asserted, it was about prior knowledge, in fact prior knowledge facilitated ‘engagement’ because you can’t engage with a task if you don’t have sufficient prior knowledge to understand what is going on.

I recommended that he read Dan Willingham’s “Why Don’t Students Like School?”

Assessment

“Levels are going and not being replaced” and if this session was all about assessment “I’d scare the pants off you”.

The photo selected above, while certainly amusing to many, was deliberately chosen to make a statement, and it reflected the general tone. You would have thought from the discussion that all educators everywhere had regarded the Levels system as perfect and had never had a bad word to say about it.

There was some good advice, for example not rushing into replacement systems too quickly, to wait and see whether there was any further guidance, and also to see how other schools were managing. And there was also some potentially valuable discussion about what schools could do, but it was conducted in the light of ridiculing the decision, rather than seriously considering the pros and cons of ways forward. “I haven’t made this up” he laughed.

Curriculum Specifics

(I bit my tongue and didn’t ask if he’d printed out all of the exam board specifications for each secondary subject to include in his page-count.)

We looked at specific areas of the curriculum, and the strong impression of the changes was very negative. Many things were now to be taught earlier. To an “education outsider” it might make sense, he said, but educators who knew their Piaget knew that the brain developed in stages and that one couldn’t teach certain things too young. He then highlighted all the things in the English and Maths curriculum that were being moved younger – “too young for children’s developmental stages.”

Science

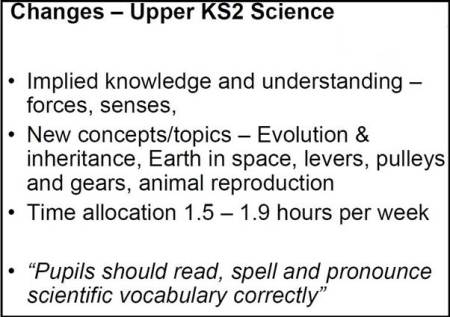

With Science came the contradiction. Rather than moving younger, some topics were being left until later. Amusingly, this was also a bad idea. This time because ‘young children had really enjoyed studying those particular topics at that age’.

There was also a concern that conducting “formal” experiments was being left until later in the new curriculum. It was explained that younger children would only be required to conduct ‘explorations’ not ‘experiments’. I couldn’t help but think that had it been the other way round i.e. if the current curriculum had exploration, and the new curriculum was demanding more formal experimentation, we would have heard that the children were too young for ‘formal’ work.

What were the problems here, asked the trainer, drawing our attention to ‘evolution’. “It’s teaching RE!” exclaimed our earnest ant-Goveite, “Yes!” he agreed heartily. He explained we can’t teach evolution in case it is against the religious beliefs of some of the children. He gave ‘Muslim children’ as an example of those who couldn’t be taught such things in Y6. And ‘inheritance’? Well that couldn’t be taught because an adopted child might realise they were adopted because of their and their parents’ eye colour.

My Thoughts

My impression from governor training sessions is that many trainers are very keen to tell us what to think. The previous course I attended was very similar, the trainer laid out her ‘philosophy’ from the beginning and provided us with unsupported, unreferenced ‘facts’ and diagrams to prove her point of view. This isn’t an approach I take to terribly well. I do think we are old enough by now to be presented with “the facts” as objectively as possible and be left to draw our own conclusions.

The trainer is absolutely entitled to think what he likes about Gove, education policy, pedagogy, the national curriculum etc. However, as governors, we needed to have a run through of the main changes, including a heads-up of any contentious issues, but without the ideologically based opinion and derision; he didn’t once mention evidence. We needed guidance as to our role as governors ; what questions should we be asking of the Headteacher and SMT; what sort of answers should we get. Instead we were told to go back to our colleagues and tell them that knowledge was akin to the temporary leaves on a tree.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

This is really terrifying – what hope do we have if the roots of progressive ideology have gone down this far?

I’m appalled that especially governors would be indoctrinated in this way, but to my mind it does mean that teacher governors need to ensure they have the most concrete and easy-to-articulate evidence base for their conclusions if they’re to have any hope at all of countering this. Does anyone know of an easily accessible, clear summary of that evidence base or is Willingham the best man out there?

It doesn’t say much for the quality of governors that they can be indoctrinated, or that trainers think they can. Much respect to your correspondent for being intelligent and mature enough to ensure that this didn’t happen to him/her.

To anyone with a knowledge of psychology, listening to some of these people must be like a doctor listening to someone going on about the lunatic fringe of alternative medicine!

For ‘a knowledge of psychology’, read ‘a modicum of common sense’.

Blimey, the thought of not teaching evolution is a joke.

As for knowledge. I can remember vividly a lot of things I learned in primary. Edward Jenner and James Phipps (Year 4) Paul Bondin and Perpendicular Bisection (Year 5) How to solve a linear equation (Year 6) to name but a few.

The points around prior knowledge and engagement are particular relevant too.

Thank you for this important and revealing posting which I’ve flagged up to contribute to a thread dedicated to different approaches to education such as ‘discovery learning’:

http://phonicsinternational.com/forum/viewtopic.php?p=1697#1697