Here’s something to take you back. Here are the aims of the 2007 National Curriculum:

The curriculum should enable all young people to become:

• successful learners who enjoy learning, make progress and achieve

• confident individuals who are able to live safe, healthy and fulfilling lives

• responsible citizens who make a positive contribution to society.

Here’s a more detailed breakdown (not that I suggest you read it all):

Somebody on Twitter recently pointed out to me that this is not dissimilar to the aims of the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence (written in 2004 but officially implemented in 2010). Its purposes were as follows:

Our aspiration for all children and for every young person is that they should be successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens and effective contributors to society and at work.

And in more detail:

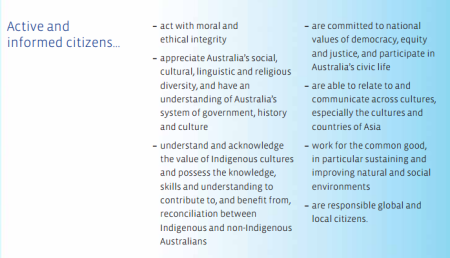

And just, in case you thought this sort of thing was only found in the British Isles, here is the Australian version, from the Melbourne Declaration of Educational Goals, made by all Australian education ministers in 2008.

These goals are:

Goal 1: Australian schooling promotes equity and excellence

Goal 2: All young Australians become:

- successful learners

- confident and creative individuals

- active and informed citizens

And in more detail:

I have commented on the English version before (here and here) but I will summarise the problems here.

- There are far too many aims, particularly if you break them down. As a result nobody could ever use it to make decisions. Almost any option would be covered by something. Inevitably, no school could directly implement these principles as written, and it is left open to a multitude of “experts” to interpret them.

- Most of the aims fail to reflect that the primary purpose of education is academic. They are about attitudes, opinions and feelings not about learning.

- The one academic category, i.e. “successful learners” contains more items about how students should learn and their attitude to learning than about what is learnt.

- A lot of this is vacuous or circular jargon. For instance, being “successful” isn’t an aim, you can only succeed if you already have an aim.

None of these problems seem to have stopped the cut and paste merchants. None of it seems to have offended the politicians. None of it seems to have been seen as contentious by the educational establishment. In the Scottish case I read here that:

…CfE (in respect of those core principles) retains all-party support in parliament. Furthermore, our research, and my recent professional interactions with teachers suggest that the teaching profession remains largely in support of those same core principles.

It’s a shame if that’s how people feel in any education system. It’s a loss of confidence in the ability to identify and directly teach what is worth knowing. But, of course, these are all from the progressive tradition in education. There is an alternative. Here, by way of contrast, are the aims of our new National Curriculum (yes, this is the entire section):

3.1 The national curriculum provides pupils with an introduction to the essential knowledge that they need to be educated citizens. It introduces pupils to the best that has been thought and said; and helps engender an appreciation of human

creativity and achievement.

3.2 The national curriculum is just one element in the education of every child. There is time and space in the school day and in each week, term and year to range beyond the national curriculum specifications. The national curriculum provides an outline of

core knowledge around which teachers can develop exciting and stimulating lessons to promote the development of pupils’ knowledge, understanding and skills as part of the wider school curriculum.

Not perfect, but a direct endorsement of the academic purpose of education. In my view, it is official permission to teach.

The International Language of Edu-Platitudes

June 23, 2014Here’s something to take you back. Here are the aims of the 2007 National Curriculum:

Here’s a more detailed breakdown (not that I suggest you read it all):

Somebody on Twitter recently pointed out to me that this is not dissimilar to the aims of the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence (written in 2004 but officially implemented in 2010). Its purposes were as follows:

And in more detail:

And just, in case you thought this sort of thing was only found in the British Isles, here is the Australian version, from the Melbourne Declaration of Educational Goals, made by all Australian education ministers in 2008.

And in more detail:

I have commented on the English version before (here and here) but I will summarise the problems here.

None of these problems seem to have stopped the cut and paste merchants. None of it seems to have offended the politicians. None of it seems to have been seen as contentious by the educational establishment. In the Scottish case I read here that:

It’s a shame if that’s how people feel in any education system. It’s a loss of confidence in the ability to identify and directly teach what is worth knowing. But, of course, these are all from the progressive tradition in education. There is an alternative. Here, by way of contrast, are the aims of our new National Curriculum (yes, this is the entire section):

Not perfect, but a direct endorsement of the academic purpose of education. In my view, it is official permission to teach.

Share this:

Posted in Commentary | 5 Comments »