Progressively Worse – A Subversive Text

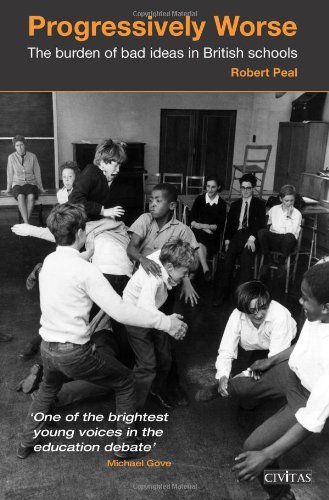

April 28, 2014This book review is a (very slightly edited) version of the foreword I wrote to Robert Peal’s Progressively worse: The Burden of Bad Ideas in British Schools. It should make it clear why I think the book is worth reading.

Few publications can claim to be subversive, but that is a fitting description for Robert Peal’s book. He has related a piece of educational history and described a debate that many educationalists, managers and inspectors will not want teachers to be aware of. It is not simply that his arguments against the influence that progressive education has on our education system will challenge many of those in a position of undeserved power and authority; he also provides the context that is lacking for so many of those who are, or soon will be, a part of our education system.

While academics and journalists (or even bloggers like myself) might talk of an ongoing and established debate over education methods between progressives and traditionalists, it is not something that one can expect to hear much of when one becomes a teacher. It is entirely possible to be trained as a teacher in a university and in schools and teach for several years without ever hearing that there is any doubt over whether teacher talk is harmful; discovery learning is effective; or knowledge is less important than skills. To inform teachers that these disputes exist is to cast doubt on the expertise of most of those who train teachers; many of those who run schools; and also those with the greatest power in education: the schools inspectorate – OFSTED. For at least some readers, this will be the first time they have heard that certain orthodoxies have been, or can be, challenged.

Of course, for the informed reader this may not be the first time such challenges to the progressive consensus have been encountered in print. The last few years have seen the publication of titles such as Daisy Christodoulou’s Seven Myths About Education, Tom Bennett’s Teacher Proof and Katharine Birbalsingh’s To Miss With Love, which have demonstrated the existence of influential voices in education expressing views many teachers have never heard before. This has been supplemented further by many, many bloggers who have been hostile to the ideological status quo. Additionally, it has also been informed by influential books from the United States by individuals such as Daniel Willingham, Doug Lemov and E.D. Hirsch. These writers, while not necessarily writing polemical or ideological tracts, have nevertheless confidently explored ideas about the curriculum, teaching methods and the psychology of learning that fell far outside the comfort zone of the English education system.

However, I believe Robert Peal is now making a unique and essential contribution to this debate by providing the political and historical context of the arguments. Neither progressives nor traditionalists can claim to represent a new development in education. With the possible exception of some of the latest evidence from cognitive psychology for the effectiveness of traditional teaching, almost all the arguments described here have been part of the history of our education system for more than five decades. Generations have fought these battles, proved their points and bucked the system, only to be airbrushed from history by an educational establishment only too keen to recycle ideas from 1967’s Plowden Report as the latest innovation. The historical chapters here analyse and present the history of those arguments in a way which perhaps most closely resembles Left Back, Diane Ravitch’s magisterial recounting of the ‘education wars’ in the United States. If this causes teachers to realise that they can find ideas and inspiration, not just in the contemporary critics of progressive education, but in the writings of Michael Oakeshott or R.S. Peters, then the educational discussion will be thoroughly enriched. The debate on education is not one limited to the present generation; it is not a scrap between, for example, Sir Ken Robinson and Michael Gove. It is a conversation that dates back, at least to the nineteenth century, in which figures such as Matthew Arnold, Charles Dickens, G.K. Chesterton, D.H. Lawrence, George Orwell, Dorothy L. Sayers and C.S. Lewis have had something to say on one side or the other. We should not let the latest iteration of the disagreement, with its talk of ‘21st Century Skills’ and ‘flipped classrooms’, blind us to that wider perspective.

A historical perspective should also save us from being convinced that this row is one conducted along narrow party political lines. While their efforts to stem the tide of progressivism may have faltered in office, it is impossible to miss the extent to which some of the voices speaking out against the education establishment were those of Labour politicians such as Callaghan, Blunkett and Blair. While the influence of progressive education seems to have been greater on the left than the right, the case against it can be made on egalitarian grounds as easily as conservative ones. Robert Tressell, the undoubtedly working-class political activist and author, wrote in The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists:

What we call civilisation – the accumulation of knowledge which has come down to us from our forefathers – is the fruit of thousands of years of human thought and toil. It is not the result of the labour of the ancestors of any separate class of people who exist today, and therefore it is by right the common heritage of all. Every little child that is born into the world, no matter whether he is clever or dull, whether he is physically perfect or lame, or blind; no matter how much he may excel or fall short of his fellows in other respects, in one thing at least he is their equal – he is one of the heirs of all the ages that have gone before.

If this point is then accepted, education, in the sense of the full entitlement to the best of our society’s culture and knowledge, is not a relic of a discredited tradition, but wealth that should be distributed to all. Comprehensive education, when viewed as an academic education for all, might represent a core principle of the left. By contrast, progressive education, with its contempt for the accumulated knowledge of mankind, is likely to work only to deprive the disadvantaged and excluded of an asset that will remain the exclusive property of the privileged and powerful. Middle-class partisans of both right and left would happily misrepresent the education debate as a mere reflection of wider political disagreements. However, many of us who identify our politics most closely with the aspirational, working-class tradition within the Labour Party are happy to campaign as firmly against the excesses of progressive education as we do against the excesses of free-market capitalism. This is for fundamentally the same reason; it increases the deprivation of the less fortunate for the sake of an ideological experiment conducted at their expense by those with little to lose personally.

So with this in mind, I welcome what Robert Peal has achieved. He has provided a much needed perspective on a debate that has been at best narrowed, and at worst hidden. It should be essential reading for anyone who wishes to engage with an argument that has raged for over a century, and shows every sign of continuing. For those unfamiliar with educational politics, appropriately it will be an education. For those who have only seen the disagreements over education described from the perspective of progressive educationalists, it will be a shock. For those within the education system who are already sympathetic to his cause, it will be a call for subversion.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Your penultimate paragraph nails it.

Why do you think OFSTED has the greatest power in education? In secondary education the exam boards have more power than OFSTED, they largely determine the curriculum content and how it is taught. OFSTED might frighten teachers when it uses the exam results to expose their weaknesses but the people that really have the power over setting the exams are AQA, Pearson and Cambridge Assessment.

The interesting thing is that we never seem to question the exams as a problem because the results are themselves considered the intrinsic traditional measure of educational success. This is the system that has been dominant for at least 50 years. Is the solution to improved education simply that we need harder exams and yet more of the same to put things right? When in a hole, stop digging.

[…] in my posts due to the emotions it raises, but I now find I must. Old Andrew’s definition in his Foreword to Peal’s book is strong on this, identifying characteristics of this ideology such as a denigration of teacher […]

“However, many of us who identify our politics most closely with the aspirational, working-class tradition within the Labour Party are happy to campaign as firmly against the excesses of progressive education as we do against the excesses of free-market capitalism.”

Very true…and even true of those of us who parted company with the Labour Party when the Labour Party parted company with Clause 4. I liked this piece very much. I have one issue however: your characterisation of politics in terms of left and right. What often pass for the ‘left’ these days are those soi-disant radicals who have more or less abandoned class as the fundamental cleavage in society and for whom politics revolve around questions of identity. These people are liberals-pure and simple; petty bourgeois to the core and ‘progressive’ as they come. They are not, however, unless it have missed something, of the left.

I’d suggest that it is they who still carry the flame for ‘progressive education’. Anybody who’s sympathies lie with the aspirational class, especially in the current climate, must by necessity favour a traditional rigorous education. If only because historically, it has consistently proven the only effective means of ensuring social mobility.

There’s obviously a side issue here: namely that, traditionally, social mobility is not a concern of socialists since social mobility becomes moot for those whose aim is the abolition of class as a meaningful concept. That said, this is the sort of argument put forward by the sort of ‘socialist’ with a trust fund and an internship at the Guardian.

Maybe, but Labour (and the Left in general) has a more practical difficulty with social mobility. The 1983 and 1987 elections proved conclusively that when people move out of the working class, they stop voting Labour and become Conservatives. More social mobility will inevitably mean fewer Labour voters and, eventually, no Labour Party at all.

Viewed in this light, progressive education can be seen as a conscious strategy to keep people in the working class, ensure that they remain ignorant and unthinking, and thereby guarantee a future Labour vote.

[…] Peal’s book Progressively Worse has stirred up the blogosphere. Old Andrew has written the foreword so I guess gets first place. Joe Kirby’s post makes me want to find a Bastille to storm […]

Thank you for this recommendation. My reading of this is that we have simply had too many people who want to leave their mark on the educational system in the UK – whether in government, think tanks, or school SLTs. The careerist impulse to be seen as bringing in change in order to “be noticed” is hugely damaging, whether it comes from successive Secretaries of State or from the latest youngster promoted to SLT after singing the accepted tune.

In a system which consistently encourages short-termism and competitive rather than cooperative behaviour, the historical context that you outline gets lost. We have known how to teach in this country for decades, but we are so obsessed with ‘progress’ that we have lost sight of the basics. Of course there is a place for new ideas occasionally, but they should never be the basis of your whole system. Of course, those purporting new ideas will probably find that they have been suggested in one form or another before.

There is no field where a relatively small number of people are not prepared to put themselves out to try and make things better (from their perspective). In a pluralist society along with freedom of speech, this is a cornerstone of democracy. Anti-progress politics ranges from luddite to conservative. The only thing that will ultimately decide the broader strategies is the ballot box. The finer details by winning the hearts and minds of teachers. Unless there is a highly centrally prescribed curriculum (the exam system already makes this so in secondary) there is likely to continue to be diversity of opinion and methods.

[…] know this isn’t new, and my contribution is available online here, but I have written the foreword for Progressively Worse by Robert […]

[…] point, and perhaps the most telling one about the inability of education to excape bad ideas. In Progressively Worse, Robert Peal quotes the following from a book written in […]

[…] to Andrew Old’s blog, Scenes from the Battleground, “In Progressively Worse, Robert Peal quotes the following from a book written in 1966: ‘The idea that our schools […]